DIRECTOR’S NOTE

How does a country choose the story to tell about itself?

If I had to choose one word to describe growing up in a country that has changed names 4 times in the past fifteen years, it would be discontinuity. Destroying the past in the name of a new beginning has become the hallmark of our history, and each new break with the past requires it’s re-writing.

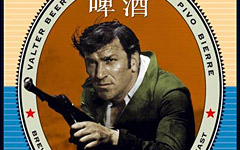

From the end of the Second World War the Story of Yugoslavia was given a visual form in the creation of Yugoslav cinema. In a sense the Avala Film studios are the birthplace of the Yugoslav illusion. For me they represent a promising point of departure – that collapsing film sets can reveal something about the collapse of the scenography we were living in.

I first went into the Avala Film studios when I was a student in film school. Sent there to get equipment for a student film, I found myself overwhelmed by the atmosphere of the place. It was immense, a ghost town of abandoned and rotting sets, out-of-date equipment, empty film lots and unemployed technicians. And nobody had ever told me anything about it.

I wanted to make a film about how films were used to write and re-write a story, to provide visuals for a narrative that became the unifying call of Yugoslavia. About the use of our filmmakers’ tools, – smoke-and-mirrors – to create the Official National Dream. The cinematic image remains as a testimony, a doorway to another time. But it is also a deception, a construct, to be analysed, and looked through.

How do we explain Yugoslavia, a country whose existence fits into a half century, book-ended by un-civil wars on either end? Yugoslavs have a passion for their cinema, perhaps founded in our passion for those same myths that have led us marching into battle too many times.

The old fortress in the heart of Belgrade houses the War Museum. Today, only a small part of it is open to the public. For those who wander in looking to spend a Sunday afternoon browsing through Serbian history, the exhibition will take them from medieval battles and kingdoms through the 1930s. The rest is closed, indefinitely. The government has asked the museum to revise the exhibition covering the Second World War, declaring it ‘over-dimensioned and biased from a communist perspective’. At a loss for official instructions on how to re-write history, its director could only shut it down. (Not to mention the fact that he doesn’t know whether to mount an exhibition on war actions and losses from the 1990s, as Serbia was never officially involved in war in Bosnia.) And so he waits for us as a society to yet again agree on our new narrative.

This became an urgent film, a response to the discontinuity all around me, a way to preserve a world that is being erased from official memory. When I look around for my childhood, every trace of it is gone, the street names changed, my school’s name changed, the neighbourhood reshaped with new office blocks. Fourteen cinemas in the heart of Belgrade have been sold and turned into cafes. Avala Films is also up for sale – and will most likely be torn down to build an elite business complex. As they disappear, I am not convinced that the best way to move forward is to pretend the past never happened.

I enter this story as a member of a new generation of Yugoslav filmmakers, one that has hazy memories of a country that no longer exists. We come of age surrounded by the ruins of something that is nostalgically referred to as a golden era, but no one has yet offered me a satisfactory insight into how it was all thrown away. We were born too late, and missed that party, but we arrived in time to pay the bill for it.

How does a country choose the story to tell about itself?

If I had to choose one word to describe growing up in a country that has changed names 4 times in the past fifteen years, it would be discontinuity. Destroying the past in the name of a new beginning has become the hallmark of our history, and each new break with the past requires it’s re-writing.

From the end of the Second World War the Story of Yugoslavia was given a visual form in the creation of Yugoslav cinema. In a sense the Avala Film studios are the birthplace of the Yugoslav illusion. For me they represent a promising point of departure – that collapsing film sets can reveal something about the collapse of the scenography we were living in.

I first went into the Avala Film studios when I was a student in film school. Sent there to get equipment for a student film, I found myself overwhelmed by the atmosphere of the place. It was immense, a ghost town of abandoned and rotting sets, out-of-date equipment, empty film lots and unemployed technicians. And nobody had ever told me anything about it.

I wanted to make a film about how films were used to write and re-write a story, to provide visuals for a narrative that became the unifying call of Yugoslavia. About the use of our filmmakers’ tools, – smoke-and-mirrors – to create the Official National Dream. The cinematic image remains as a testimony, a doorway to another time. But it is also a deception, a construct, to be analysed, and looked through.

How do we explain Yugoslavia, a country whose existence fits into a half century, book-ended by un-civil wars on either end? Yugoslavs have a passion for their cinema, perhaps founded in our passion for those same myths that have led us marching into battle too many times.

The old fortress in the heart of Belgrade houses the War Museum. Today, only a small part of it is open to the public. For those who wander in looking to spend a Sunday afternoon browsing through Serbian history, the exhibition will take them from medieval battles and kingdoms through the 1930s. The rest is closed, indefinitely. The government has asked the museum to revise the exhibition covering the Second World War, declaring it ‘over-dimensioned and biased from a communist perspective’. At a loss for official instructions on how to re-write history, its director could only shut it down. (Not to mention the fact that he doesn’t know whether to mount an exhibition on war actions and losses from the 1990s, as Serbia was never officially involved in war in Bosnia.) And so he waits for us as a society to yet again agree on our new narrative.

This became an urgent film, a response to the discontinuity all around me, a way to preserve a world that is being erased from official memory. When I look around for my childhood, every trace of it is gone, the street names changed, my school’s name changed, the neighbourhood reshaped with new office blocks. Fourteen cinemas in the heart of Belgrade have been sold and turned into cafes. Avala Films is also up for sale – and will most likely be torn down to build an elite business complex. As they disappear, I am not convinced that the best way to move forward is to pretend the past never happened.

I enter this story as a member of a new generation of Yugoslav filmmakers, one that has hazy memories of a country that no longer exists. We come of age surrounded by the ruins of something that is nostalgically referred to as a golden era, but no one has yet offered me a satisfactory insight into how it was all thrown away. We were born too late, and missed that party, but we arrived in time to pay the bill for it.